Click on photos to enlarge.

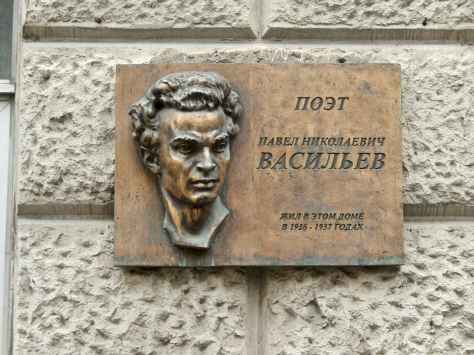

It seems to be a time of discovering poets for me. A few days ago it was Richard Ter-Pogosian. Now it is another. I was walking through my former city of Moscow yesterday and happened upon a plaque I didn’t know commemorating a poet I’d never heard of – Pavel Vasilyev, who lived in this building at 26 Fourth Tverskaya-Yamskaya Street in 1936 and 1937. Yes, you probably guessed right: that latter date is also the poet’s year of death. The meat grinder year. The year of blood. The year of hatred, lies, villainy and infamy. What will ever be done to wash away the sins of that year? Nothing? Can nothing wash those sins away? And what happens if that is true?

But let’s narrow the conversation a bit; bring it back to this new poet in my life. These days, with our instant access to information, it is not difficult to begin understanding the stature that Vasilyev enjoyed for a brief time in his life. The number of poets, writers and others singing his praises in the late 1920s, early 1930s is more than merely impressive – it is downright imposing. As Valentin Antonov wrote in an eye-opening blog in 2009, you can begin the list with Alexei Tolstoy, Anatoly Lunacharsky, Ryurik Ivlev and Vladimir Soloukhin. Our purposes today will be served by Boris Pasternak, who wrote in 1956 (presumably taking part in Vasilyev’s “rehabilitation,” which occurred that year):

“At the beginning of the 1930s Pavel Vasilyev impressed me upon first discovery approximately as had Yesenin and Mayakovsky before him. He was comparable to them, particularly to Yesenin, by his creative expressiveness, the power of his gift and his great, infinite promise, because he lacked the tragic explosiveness, which internally cut short the lives of the latter two, and he commanded a cold composure allowing him to control his turbulent instincts. He possessed that bright, happy and quick imagination, without which great poetry does not exist, the likes of which in such abundance I have never seen again in all the years that have passed since his death.”

That is no rote, routine recommendation. Pasternak here, in just a few lines, places Vasilyev among (and to some extent, above) the greatest poets of his time.

Wolfgang Kasack, the great German scholar, called Vasilyev’s poetry “antiurban, erotic and associated with the free life of the Cossacks.” Later in his entry in his Dictionary of Russian Literature since 1917, he adds: “Vasilyev’s poetry is characterized by an earthy, graphic power. Fairy-tale elements mingle with Cossack history and a revolutionary present. Strong characters, powerful animals, fierce action and the colorful landscape of the steppes are expressively combined in scenes that create great forward momentum with varied rhythms. Bloody revolutionary events experienced in Vasilyev’s childhood are presented without reference to historical persons or incidents.”

Vasilyev’s stance – and one did have to have a stance in those years; it was virtually impossible to stand and watch tumultuous events pass by – was a confused one. As an 11 year-old schoolboy he wrote a poem dedicated to Vladimir Lenin that was picked up and turned into a song by his teacher and classmates. He seemed to sing the praises of the Revolution at times, while at others he was clearly at odds with its consequences. By the early 1930s he was constantly running into trouble. His fate was probably sealed when Maxim Gorky (yes, that slipperly ol’ Maxim Gorky again) in 1934 accused him of “drunkenness, hooliganism and violating the law on residence registration.”

What the hell? Was Gorky playing the role of the pot calling the kettle black? I don’t know; I’ll have to look into this some day. But here are some of the facts of the end process:

Vasilyev was first arrested in 1932, although was released before long. Gorky jumped on his back in 1934 and, surely consequently, Vasilyev was kicked out of the brand-new Writers Union in January 1935. Six months later he was arrested again, this time for engaging in what, by all accounts, was a nasty, drunken, public fight with a poet known as Jack (Yakov) Altauzen. Judging by the record, Vasilyev’s antisemitic views were well known, and this brawl appears to have been a flare-up of racist behavior. Vasilyev was released early again, in 1936. In February 1937 he was arrested still again for the supposed crime of belonging to a terrorist group whose purpose was to assassinate Joseph Stalin. He was condemned to be shot and the sentence was carried out July 16, 1937, in the Lefortovo prison. Similar to his contemporary, Vsevolod Meyerhold, his remains lie in an unmarked grave in the Donskoi Monastery.

Pavel Vasilyev (1909-1937) was a restless man. Even with his family as a youth he traveled often from town to town. His father was a teacher and held many different jobs. The poet was born in the town of Zaisan in what is now known as the Republic of Kazakhstan. Other cities figuring in his biography are Pavlodar, Sandyktav Station, Atbasar, Petropavlovsk, Omsk, Vladivostok, Khabarovsk, Novosibirsk and Moscow. He spent time as a fisherman and prospector on the Irtysh and Selemidzha rivers. He also worked as a journalist, leading him toward the life of writer and poet. His first published poem was called “October,” and was printed in Vladivostok on Nov. 6, 1926. His poems were soon picked up by many of the top publications in the Soviet Union, including Izvestia, Novy Mir, Literary gazette, Ogonyok and many others. At the same time, much of his work could not be published. For example, in the early 1930s he wrote a series of ten folkloric, historical verse epics, although only one, The Salt Riot (1934), saw the light of day. Either because of his poetry, his personality, or his intolerant world view – or, perhaps, because of all three together – he eventually came upon his downfall. It is accepted knowledge that Vasilyev was the prototype for the main character, an antihero, spy and ruffian named Andrei Abrikosov in Ivan Pyryev’s popular film The Party Ticket (1936). Note that he was portrayed here as a spy a year before he was executed for being a spy…

I don’t know enough about Vasilyev to take sides for or against him in regards to his character or lack thereof. I do, however, see a depressingly familiar case of a talented, unusual person being singled out by the in-crowd and turned into a victim and a scapegoat. The story of Pavel Vasilyev may be messy and paradoxical. But it ends with a gunshot – probably to his head – which gives him certain rights in retrospect.

Here is a poem written in February 1937, presumably after he had been arrested:

Red-breast finches flutter up…

So soon, to my misfortune,

I’ll see the green eye of the wolf

In hostile northern lands.

We shall be heartsick and forlorn,

Though fragrant as wild honey.

Unnoticed, time frames will collapse

As gray enshrouds our curls.

And then I’ll tell you, sweet:

“The days fly by like leaves upon the wind,

It’s good that in a former life

We found each other then lost it all…”